I’m happy to announce that Joe Roe and I just published a paper in Internet Archaeology that explores collaborative practices in archaeological open source software development. This paper has been in development for a while, and we’re glad to finally release our work.

- Version of record: https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.67.13

- Postprint: https://zackbatist.info/openarchaeo-collaboration

- Research compendium: https://github.com/zackbatist/openarchaeo-collaboration

- Zenodo archive: https://zenodo.org/records/12752060

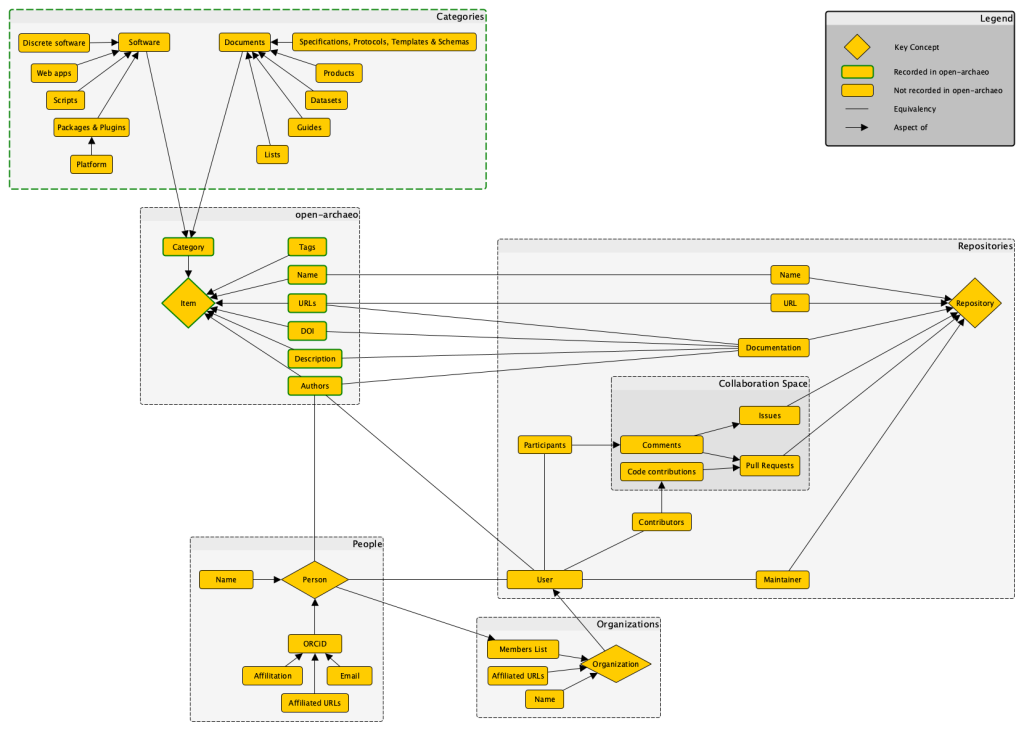

To briefly summarize: we investigated the under-explored practices involved in research software engineering in archaeology, with an emphasis on collaborative experiences involved in open source software development. We identified not only what kinds of software archaeologists are making, but how archaeologists create these tools as part of a broader community of practice. We conducted exploratory data analysis and network analysis on data from open-archaeo, supplemented with additional data pulled from the GitHub API, to trace how archaeologists use various languages, forges, licenses and supporting features (e.g. issues, stars, pull requests), and to discern trends regarding projects’ longevity, degree of community participation, and overall structure of collaborative ties.

Open archaeology, open source? Collaborative practices in an emerging community of archaeological software engineers

Surveying the first quarter-century of computer applications in archaeology, Scollar (1999) lamented that the field relied almost exclusively on “hand-me-down” tools repurposed from other disciplines. Twenty five years later, this is no longer the case: computational archaeologists often find themselves practicing the dual roles of data analyst and research software engineer (Baxter et al. 2012; Schmidt and Marwick 2020), developing and applying new tools that are tailored specifically to archaeological problems and archaeological methods. Though this trend can be traced to the very earliest days of the field (Cowgill 1967), its most recent manifestation is distinguished by its apparent embrace of practices from free and open source software. Most prominently, since around 2015, there has been a rapid uptake of workflow tools designed for open source development communities, such as the version control system git and associated online source code management platforms (e.g. GitHub, GitLab). These tools facilitate collaboration among developers and users of open source software using patterns that can diverge quite radically from conventional scholarly norms (Tennant et al. 2020).

In this paper, we investigate modes of collaboration in this emerging community of practice using ‘open-archaeo’, a curated list of archaeological software, and data on the activity of associated GitHub repositories and users. We conduct an exploratory quantitative analysis to characterize the nature and intensity of these collaborations and map the collaborative networks that emerge from them. We document uneven adoption of open source collaborative practices beyond the basic use of git as a version control system and GitHub to host source code. Most projects do make use of collaborative features and, through shared contributions, we can can trace a collaborative network that includes the majority of archaeologists active on GitHub. However, a majority of repositories have 1–3 contributors, with only a few projects distinguished by an active and diverse developer base. Direct collaboration on code or other repository content—as opposed to the more passive, social media-style interaction that GitHub supports—remains very limited. In other words, there is little evidence that archaeologists’ adoption of open source tools (git and GitHub) has been accompanied by the decentralized, participatory forms of collaboration that characterise other open source communities. On the contrary, our results indicate that research software engineering in archaeology remains largely embedded in conventional professional norms and organizational structures of academia.